The Magic of Haida Gwaii

by Wade Davis, National Geographic Explorer in Residence

Something magical was in store when we docked at Charlotte City just after seven, with mist over the water, and found waiting for us Linda Tollas, our Haida friend and interpreter for the coming days. Sister of Terry Lynn Davidson, legal counsel for the Haida nation, and sister-in-law of Robert Davidson, one of the finest of Haida artists, Linda is the daughter of Mabel Williams, granddaughter of Sarah Price, and great granddaughter of Susan Williams, a legendary matriarch who died at the age of 109. Linda’s native name translates as “the one who sits regally.” To be with her really is to be with Haida royalty and for this we are very grateful.

Haida Gwaii, the misty islands, how dramatically they have changed over the last years! The multinational timber companies that once dominated the economy and dictated public policy are gone. More than half of the land is protected. What timber production remains is in the hands of the Haida, an outcome that would have been unimaginable thirty years ago.

The economy measured by conventional indicators is weaker. The population of Sandspit, long an industry town, has dropped from 700 to 200. Government agencies, including the Ministry of Forests, which once supported sixty families in Charlotte City alone, have indiscriminately shed employees.

But little of this affected the Haida, who were never beneficiaries of a timber boom that implied only the destruction of their homeland. To a remarkable degree they lived outside of the formal economy, dependent on the sustainable resources of the land - salmon, halibut, venison, crabs, octopus, seaweed, herring roe, clams, sea urchins, berries, abalone and cedar. “When the tide is out,” the Haida like to say, “the table is set.”

The collapse of industrial logging has in fact coincided with a revitalization of Haida culture that few could have anticipated when the whine of chainsaws and yarders dominated all sounds in the forests.

There is no better place to take measure of this astonishing transformation than the Haida Heritage Centre at Kay Llnagaay, a museum and shrine to Haida culture located just east of Charlotte City. Home to the finest collection of argillite carvings in the world, as well as contemporary art and scores of wooden and stone artifacts recovered from ghostly villages scattered throughout the archipelago, the Haida Heritage Centre is the symbol of the resurrection of Haida culture.

It is also the very site where Bill Reid in 1975 accepted Guujaaw as his apprentice. Together they carved and raised the first totem pole to be erected in more than a century. It was as if a new wind had blown through the hearts of the Haida. Since then totem poles have sprung up by the score, symbols of rebirth but also signs of a new economy based on the creation of art of the highest aesthetic quality, both for sale and ritual activities- masks, cedar bent boxes, gold and silver jewelry, exquisite prints, button blankets and robes.

From the HHC we drove north, along the eastern shore of Graham Island, past the hanging rock, through the fields of Tlell, over the river and alongside the cabin where on one fateful night some forty years ago Guujaaw, destined to be head of the Council of the Haida Nation, and Thom Henley, Huckleberry to his friends, got out the maps, scratched a boundary across a map of the islands and vowed to save everything south of the line. Most laughed it off, said it could never be done, but today that line is the northern frontier of Gwaii Haanas, the national park we will begin to explore tomorrow.

The bogs of Naikoon carried us past Port Clements at the head of Masset Inlet, home of the Golden Spruce and the White Raven, both long dead, destroyed by man, north to Kitkatla Slough, a bird sanctuary where last week alone alighted 75 Sandhill cranes. Crossing a causeway we reached Old Masset, home to the Eagle moiety.

Linda spoke.

As a Raven, and a descendant of the people of Skedans, she would have in the old days been betrothed in an arranged marriage to an Eagle, securing for her family a reciprocal bond in kinship and commerce. But she had chosen instead to marry in the modern way, a love marriage with a non-Haida she met at a logging camp. The marriage did not last but the consequences endured. By marrying a white man she lost her legal status as a native person. Had a Haida man, she explained, married a white woman, he not only retained his status, but his wife became Haida as well. This, Linda explained, was but another means by which the dominant white society worked to undermine the traditional social structure of the Haida, based as it was on matrilineal descent. In losing her status Linda found herself into limbo, both psychologically and materially. Ostracized socially, cast adrift from kindred, denied even the right to gather food from traditional sources, she found herself lost in translation. She had little choice but to leave the islands, which she did, not to return for 25 years.

In Old Masset we were welcomed at the long house of Christian White, an exceptional Haida carver of argillite, canoes and totem poles, and one of the leading cultural figures of Haida Gwaii. With his wife Candace, an anthropologist and teacher of the Haida language, he leads a cultural revival based on song and dance, ritual and dreams, all of it rooted in the art of creation that is the essence of the Haida, an edge of steel transforming a cedar log into symbols of the eternal.

One dance was that of shark, mother of dogfish. Another recalled a gesture of peace, a warrior in movement leaving eagle feathers in his wake, just as shamans quelled the wrath of the sea by scattering down upon the waves. Christian reminds us that these songs and dances were the currency of the Haida. Material goods could come and go, happily, without regret or attachment in the reciprocal gift exchange that was the potlatch. The songs and dances by contrast were actual wealth, real and meaningful possessions, a kind of prayer for the well-being of the entire community that could only be performed by those who had inherited the right to bring these sacred melodies and movements into the world.

Christian later brought us to his carving shed, a workshop where cedar logs sixty feet long were being transformed into totem poles and canoes, with paddles carved from yew wood, fish nets spun from cedar bark and nettles. Outside, with a fine mist in the air, he shared the stories of the poles he had put up for his family and ancestors. Each account was an epic tale, not to mention a huge expense. Each pole required 500 men to erect, a thousand more to bear witness to the event, and all had to be fed and gifted for the event to shine as a community memory that would never fade.

House poles, carved flat in the back to rest easily against the facade of the long house, displayed the heraldic crests of the family, Raven, Eagle, Frog, Bear, much as an aristocratic European family might display its coat of arms. Memorial poles by contrast were carved in the round to be observed from all sides. These too were decorated with crests and heraldic emblems, doing honor to the one being remembered. Mortuary poles were burials, each with a cedar box held high off the ground, in which would be placed the bones of the deceased. Finally there were story poles. These, as the name suggests, recalled a narrative, a powerful and meaningful moment in time. All of these poles, Christian noted, took months to create. Each had to be buried nine feet in the ground, in a bed of stones, as had always been done. Christian had no time for innovation or short cuts, the use of cement or iron bars.

Hospitality is a universal trait of culture at which the Haida excel. At Christian’s Canoe House a dozen women prepared a feast, dinner for sixty, even as we all slipped away to visit Jim Hart, arguably the greatest of all living Haida artists, who lived just up the road. Jim and his family welcomed us into his home, and with immense grace and warmth he spoke of his vision for Haida art. Among the most prolific of Haida artists, he shared the outline of a dozen new projects, each more monumental and ambitious than the last. A new pole to be carved out of a 60’ log, a story to be told of the residential schools, and a new era of hope, reconciliation and forgiveness for all. A large sculpture of three Haida watchmen, carved in the round from a massive block of yellow cedar and destined to be transformed into bronze.

Jim’s work is internationally renowned, and his pieces are to be found in museums and galleries throughout the world. To have been invited into his home, in the presence of his family, to watch as he carved into wood, to hear how he honed his thoughts, each a story as sharp as a knife, was a privilege that none of us will forget.

As the rain began to fall, we returned to the Canoe House for a final blessing from Christian and his family, a glorious spread of salmon, herring roe, and seaweed, and crab prepared for us with kindness and generosity by some of the most wonderful people we will ever have a chance to meet.

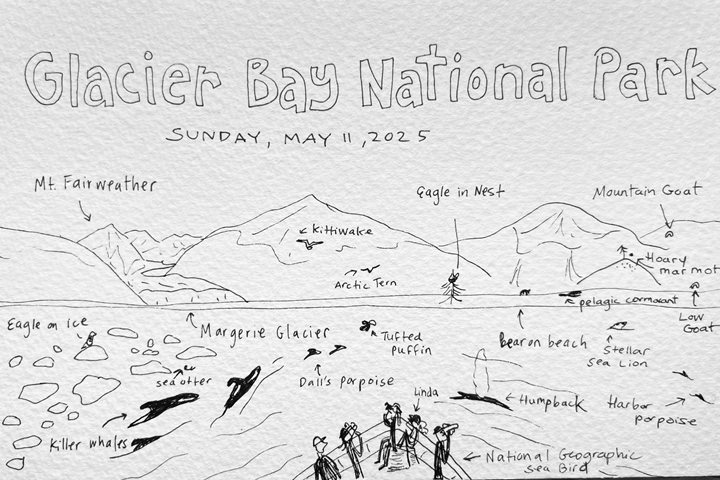

A final passage back to the ship. Sandhill cranes in the meadows of Tlell, eagles hovering over the hanging rock, mist over the waters, home to the ship.